Examining the crucial components of quality in clinical autopsies: reflections as correlates of quality health care and implications for health professionals

Akinwumi Oluwole Komolafe1* and Abiola Olubusola Komolafe2

1. Department of Morbid Anatomy and Forensic Medicine, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria

2. Department of Nursing Science, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Dr Akinwumi Oluwole Komolafe, Department of Morbid Anatomy and Forensic Medicine, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ilesa Road, Ile-Ife, Osun State PMB 5538 Nigeria. Telephone: +234 803 355 7741 Email: abiolakomolafe2016@gmail.com, abikomo@oauife.edu.ng

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

|

Submitted: |

14 June 2021 |

|

Accepted: |

23 June 2021 |

|

Published: |

1 January 2022 |

Abstract

The clinical autopsy is gradually becoming extinct due to the fear of litigations by clinicians who feel threatened by possible worrisome revelations through the autopsy. The aim of this study was to assess the most important components of clinical autopsies, as yardstick for assessing quality clinical practice. A retrospective review of documentations in clinical autopsy reports of 75 full post-mortem dissections were conducted. Attention was paid to the crucial components of a quality autopsy. The results revealed that 60% of the cases were males while 40% were females. The leading causes of death were raised intracranial pressure (26.7%) and septic shock (26.7%). Correct diagnoses were made in 66.7% of cases and there was 0% compliance with the guideline for clinicopathological write-up. The prime position of the post-mortem examination as the medical audit tool for the quality of care in clinical practice remains unassailable. The autopsy remains the gold standard for assessing the competence of health professionals of all levels and could provoke many questions about decisions taken and care given in the deceased patients care. Thus, the autopsy as a quality evaluation tool must measure up to the highest quality standard possible.

Keywords: clinical autopsies; diagnostic concordance with clinical practice; quality control

Introduction

The provision of quality care centres on correct clinical diagnoses. The clinical diagnoses provide guidance on patients' health problems and the care needed(1). When clinical diagnoses are missed or incorrect, the medical and nursing care may be ineffective resulting in preventable deaths in many cases(2). The autopsy though a gradually vanishing medical service remains the gold standard for assessing the quality of medical practice(3). The post-mortem examination evaluates the appropriateness or otherwise of the decisions taken during the antemortem care of patients by the clinicians and other care givers(4). The autopsy also verifies the judgements and conclusions of investigative departments such as laboratory medicine and radiology. It remains the best means of incontrovertible clinicopathological correlation. If the autopsy is an assessor of excellent and quality medical practice, then it stands to reason that the autopsy itself must conform with the highest standards possible in terms of conduct, techniques, personnel, interpretation, maintenance of the chain of custody of retained tissues, documentation, timely delivery of reports and necessary associated correspondence.

The autopsy by its pivotal position and veritable standards in assessing clinical care then needs to be consistently of the highest quality possible. The post-mortem examination is a multistage procedure consisting of several processes and stages that may not be outrightly quantifiable. The techniques of dissection, the objectivity of morphological analysis may not be easily verifiable but the documentations would in retrospect raise questions about the quality of the post-mortem examination(5). This study being retrospective in nature could not assess all the afore-mentioned quality elements but by virtue of assessing the components of the autopsy report and documentations, the authors sought to contribute to affirming the place of quality in autopsy practice.

This study aimed to ascertain the compliance with quality control defining standards in full post-mortem examinations in patients who died on admission in the hospital.

Materials and Methods

The study was a retrospective review of clinical autopsy reports in the practice jurisdiction of pathologists of the Department of Morbid Anatomy and Forensic Medicine, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria, over 9 years (2011 – 2019). The study analysed the clinical autopsy reports in order to ascertain for documentation of the most important aspects of a quality autopsy procedure such as the autopsy diagnosis of the primary disease that initiated the sequence of events resulting in death, clinical history, working clinical diagnoses, autopsy findings, provisional anatomical diagnoses, final anatomical diagnosis, clinicopathological correlation and cause of death. It also ascertained the correct and incorrect diagnoses based on autopsy findings, define the primary disease responsible for the sequential morphological changes in each autopsy as well as the immediate causes of death in the autopsies. All cases with incomplete data were excluded from the study and the data obtained were analysed using descriptive statistical methods.

Results

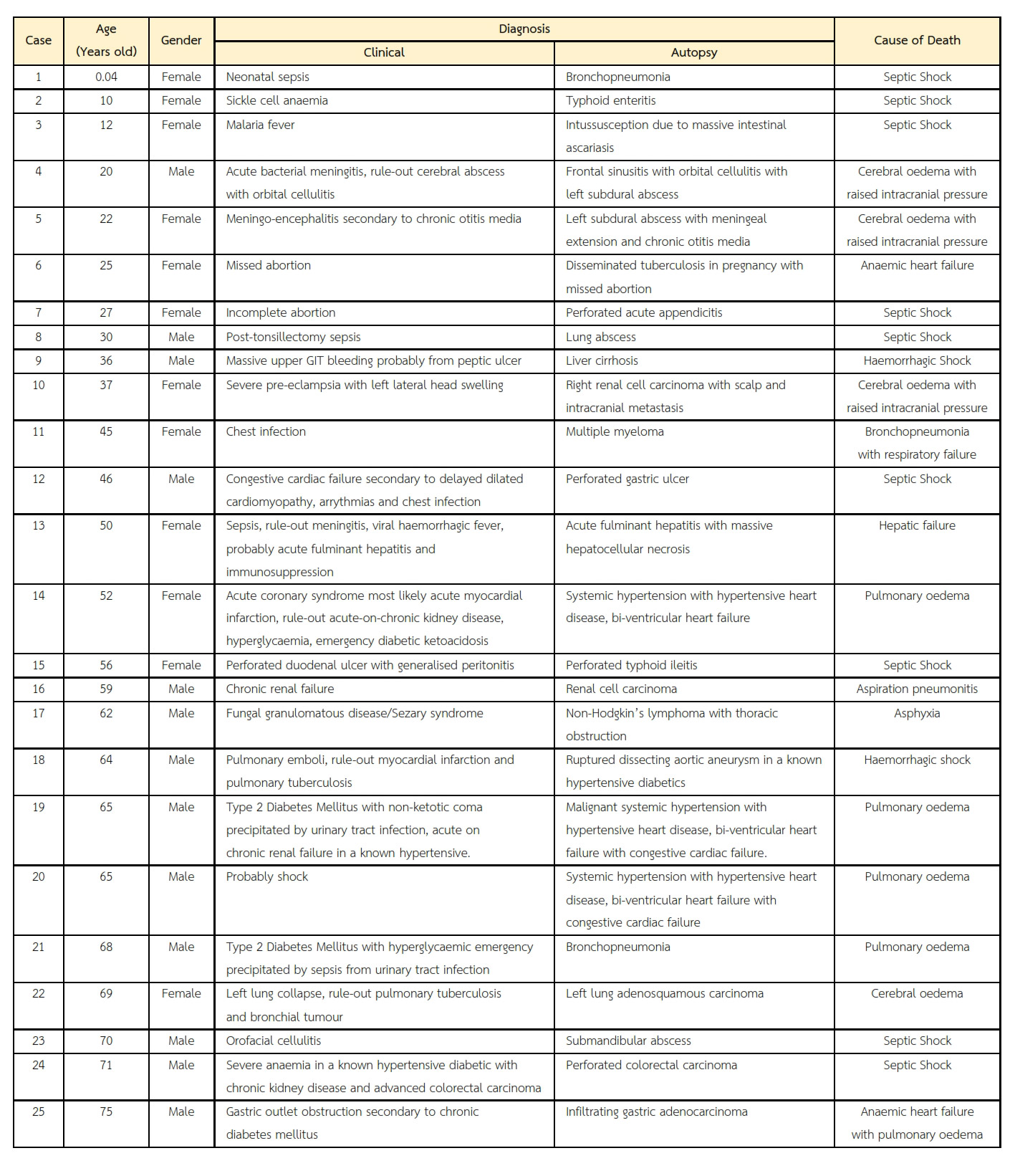

Out of the autopsy cases, only seventy-five cases met the inclusion criteria. There were 45 (60%) males and 30 (40%) females making a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. There were 50 (66.67%) cases of correct clinical diagnoses and 25 (33.33%) cases of incorrect clinical diagnoses. Thirty-two out of 75 (42.67%) cases with correct clinical diagnosis were made in males (Tables 1 and 2). There were 21 cases of systemic hypertension, 7 cases of perforated typhoid ileitis, 4 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis, 3 cases of renal cell carcinoma, 3 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, 3 cases of perforated gastric ulcer, 2 cases of perforated gastric adenocarcinoma, 2 cases of pyogenic meningitis, 2 cases of liver cirrhosis, 2 cases of lobar pneumonia, 2 cases of organophosphate poisoning, 2 cases of sickle cell anaemia and one case each for submandibular abscess, subdural abscess, lung abscess, perforated colorectal carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma of the left lung, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, road traffic accident, perforated acute appendicitis, chronic glomerulonephritis, gestational choriocarcinoma, chronic myeloid leukaemia, acute fulminant hepatitis, multiple myeloma, intracerebral abscess, bronchopneumonia, septic abortion, intussusception, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, ruptured dissecting aortic aneurysm, chorioamnionitis and post-operative sepsis.

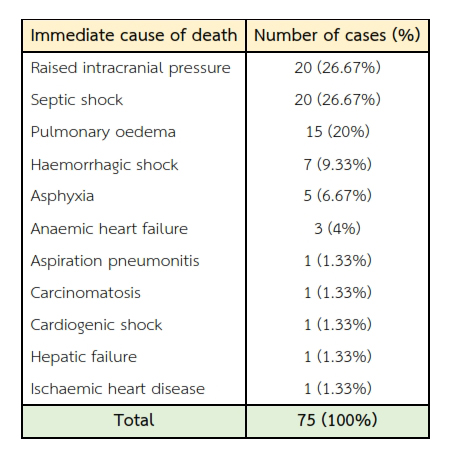

Of the causes of death, there were 20 (26.67%) cases of raised intracranial pressure, 20 (26.67%) cases of septic shock, 15 (20%) cases of pulmonary oedema, 7 (9.33%) cases of haemorrhagic shock, 5 (6.67%) cases of asphyxia, 3 (4%) cases of anaemic heart failure, one (1.33%) case each of aspiration pneumonitis, carcinomatosis, cardiogenic shock, hepatic failure and ischaemic heart disease (Table 3).

Table 1 Age and gender distribution of correct and incorrect clinical diagnoses. Approximately 66.67% of cases had correct clinical diagnoses and the largest percentage (42.67%) of these cases were made in males.

Though all of 75 cases showed documentation on the biodata, clinical history, working clinical diagnosis, provisional anatomical diagnosis, final anatomical autopsy diagnosis of the primary and initiating disease condition, cause of death and clinicopathological correlation, all the cases had incomplete write-up of the clinicopathological correlation, as the reasons for wrong clinical features were not accounted for. Medicolegal issues were not mentioned. None of the reports had the documentation of the turn-around time or the official communication of the report to the clinicians by means of an autopsy correspondence.

Table 2 The discrepancy between clinical and autopsy diagnoses. Based on 25 cases of incorrect clinical diagnoses, the missed diagnoses mostly consisted of infections in the elders (particularly the seventh decade of life), malignancies and hypertensive complications.

Table 3 Immediate cause of death established by the autopsy. Three leading causes of death were raised intracranial pressure, septic shock and pulmonary oedema.

Discussion

This study examined the quality of the post-mortem examination as a core component in overall patient care. This was a retrospective study aimed at verifying the extent of compliance with strict attention to details that constitute autopsy quality. The only means to conduct an assessment of quality in such a retrospective study like this was by systematically scrutinising the documentation of the autopsy findings in the authenticated and archived autopsy reports. Scordi-Bello et al in their study underscored the prime position of the autopsy in tracking major errors in antemortem clinical care which if detected could have altered the course of disease significantly(4). This finding of significant errors at autopsy, some of which could have altered patient's outcome significantly was corroborated by Shojania et al in their series in which they found major error rates of 23.5%(5). Komolafe et al also posited that some of the misdiagnosed conditions are common ailments and indeed treatable benign conditions(6). This opinion is further strengthened by Nwafor et al in their study who opined that morbidity and mortality patterns are reflections of disease burdens(7). It then means that the post-mortem examination, if properly carried out could translate to experience and knowledge that could help in subsequent patients' care. The autopsy has no doubt over the ages played eminent roles in medical care such as confirming the working clinical diagnosis and if the clinical diagnosis is wrong, the autopsy shows convincing reasons why the diagnosis was wrong; the progression of disease, the complications, the stage of the disease at death, and may also highlight or detect medicolegal issues beforehand(8). While our study showed a male to female ratio of 1.5:1, Nwafor et al found a male to female ratio of 1.3:1 while Komolafe et al found a male to female of 1.6:1. Both studies show a male preponderance in gender involvement in diseases. This may be due to genetic differences and sociocultural demands on males globally which makes the male gender vulnerable due to exposure to the vicissitudes of life. Pakis et al found a concordance rate of clinical and autopsy diagnoses in 49.1% while the discordance rate was 14.7%. Pakis further highlighted that ischaemic heart disease resulting in myocardial infarction, bacterial pneumonia and ruptured aortic aneurysm were the often-missed diagnoses(9). However, Komolafe et al in their study found that the often misdiagnosed cases were systemic hypertension and the associated complications, lobar pneumonia, intracranial haemorrhage, hepatocellular carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma(8). Baker found discordance rates in 39.7% of their autopsies. Komolafe et al had found a concordance rate of 64% compared to a discordance rate of 36% in an earlier study of medical errors discovered at autopsy that could precipitate medical litigations(6). Loughrey et al in their study established that major discrepancies are encountered at post in 10% of cases(10). Daramola et al found 11% of discrepancies from their study(11).

The major causes of death in this study terminally were septic shock, raised intracranial pressure, pulmonary oedema and haemorrhagic shock accounting for 26.7%, 26.7%, 20.0% and 9.3%, respectively. The leading role of infections as a leading cause of death in our findings were corroborated by Akinwusi et al who asserted from their studies that infections was a leading cause of sudden death(12). Komolafe et al found that infections were most likely to result in death when they were missed or misdiagnosed(6). The finding of raised intracranial pressure as a major cause of death terminally due to cerebrovascular accidents from long-standing systemic hypertension is corroborated by Akinwusi et al who found the complications of hypertension as the cause of death in 48.3% of sudden deaths as well as Komolafe et al who found that systemic hypertension were the second most common reason for misdiagnoses found at autopsy(8,13).

The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Autopsy Working Party stressed the role of the autopsy in patients' care and outlined the most important elements of good autopsy practice(14). Since the care of patients is multidisciplinary, it is therefore imperative for all health professionals to see optimum healthcare delivery as a team responsibility. The physician and nursing personnel are the closest to patients of all heath care providers. Both owe the anatomical pathologist strict documentation of antemortem events as the basis of reference for the pathologist. The role of forensic nursing personnel in counselling for the autopsy, ensuring standards and communicating findings to other nursing personnel and patients' relatives is crucial in qualitative autopsy practice(15,16). The pathologist also owes the management team the duty of feedback from the post-mortem examination or inviting or interacting with the team to clarify grey areas and correlate morphological features with clinical presentation. The issues of quality control and assurance in autopsy pathology is a subject that warrants interminable interrogations until all hidden facts are excavated, considering the vital role the autopsy plays in patients' management(14). Discrepancies in the concordance and discordance rates may be due to variable experiences of physicians and nursing personnel in the management team in different medical facilities across diverse nations. Missed diagnoses may be the subject of medical litigations with serious consequences for health professions in terms of integrity, finance and career. These negative consequences are well captured in the travails of healthcare professional exemplified by R v Hadiza Bawa-Garba(17). Di Nunno et al emphasised the role of quality autopsy in ascertaining the exact cause to death, assessing the quality of care given antemortem and also excluding professional liability in malpractice suits(18).

The role of the hospital autopsy is time-honoured with veritable benefits proving that death though irreversible is not final in terms of its numerous contributions to the effectual practice of medicine(19,20). Every patient dead or alive deserves the right diagnosis and this should be properly documented. For the dead that had post-mortem examinations performed on them; there are gains that are practical, memorable academic lessons cum experiences and sometimes theoretical that helps us to audit our practice extensively with a view to extrapolating the lessons learnt to the management of living patients so as to prevent worsening morbidity, improve the quality of life and delay mortality(21,22). The post-mortem examination is the key to understanding with certainty the evolution of diseases and therefore brilliantly writing the disease history in retrospect, correlation of clinical features with organ structural changes, predicting the likely outcomes in the future when new cases present with similar features, staging the disease in the living and dead, effectively correlating results and reports of ancillary investigations with autopsy findings(14,23).

The contributions of the dead to knowledge and by extension the practice of medicine is seemingly endless as it includes auditing the skills and competence of all members of the management team(2,24). This is because the findings at autopsy is used to evaluate the judgement of the medical and paramedical personnel involved in the management of the patient, documentations and decisions taken by them on the patient(25). The autopsy is thus the reveal of undocumented secrets and ultimate arbiter where the circumstances as well as the mechanisms of death are brought to the fore. The post-mortem examination also enables us to clarify and resolve issues which arise in the course of the management of patients which have immediate and remote medicolegal importance and significance. This includes rationally, logically and systematically ruling out beyond every reasonable doubt the differential diagnoses and mimics which generated conflicts in the course of the management of the patient(19,20,26). Post-mortem clinicopathological meetings based on autopsy findings would enable medical, nursing personnel and all that participated in the management of the patient to prepare ahead as fact witnesses, should medicolegal issues arise.

There is no doubt that the living gains immensely from the documentations of post-mortem examination which are actually products of diverse modes of experience garnered over many years. Thus, these invaluable gains of the living from the postmortem examination of the dead include understanding the aetiology and therefore the nature of disease, its evolution and pathogenesis, circumstances unique to the patient that may vary the pathogenesis and patterns of disease expression, the most likely disease outcomes, progressive stages and ultimate prognostication.

The central role of the autopsy compels us to put appropriate structures in place to properly conduct all aspects of the autopsy with professional competence and utmost excellence(27). This then makes quality control issues in autopsy pathology highly imperative(28,29). Items of major importance in quality control include establishing that an autopsy was indeed performed by competent personnel(30), the safety of medical personnel in the autopsy suite such as strict compliance on a routine basis with basic safety protocol(31,32), the technical approach or method of dissection, the appropriate interpretations given, flawless biodata, vital statistics of major organ-systems (measurements and weights give us the idea of the extent of deviation from normal sizes and weights), appropriate description of the organs before conclusions to the right diagnosis, provisional anatomic summary, final anatomical summary and rational cum systematic clinicopathological correlations. Unfortunately, despite the tangible benefits of the autopsy, there is an increasing worrisome decline in the number of autopsies been performed worldwide due to diverse reasons some of which include lack of trained personnel, over-reliance on pre-mortem investigations to establish the cause of death and fear of litigations among clinicians(26,33–35).

The autopsy if properly conducted should generate moral, ethical and professional questions which the pathologist, requesting clinician and all relevant stakeholders must answer sincerely. Such questions include:

- What was the primary disease that initiated the sequence of events that culminated in the death of the patient?

- What is the cause and circumstance of patient's death?

- Were the clinical deductions compatible with the autopsy findings?

- Was the working clinical diagnosis, correct?

- Was it a misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis?

- Why was the diagnosis missed?

- What facilities for investigations are not available for proper management?

- What level of doctors and nurses managed, performed surgeries and procedures, or interpreted laboratory, radio-diagnostic and other reports?

- Could the outcome have been better in the hands of more experienced and more qualified personnel?

- Do we need re-training or more exposure for some of our staff?

- Have new equipment for investigations really helped our sense of judgment?

- Is the hospital equipment duly and periodically calibrated?

- Are personnel well trained to handle the equipment and deploy them appropriately to the needs of patients?

- Which staff is the "weak link" in the managements of cases (wards, units, clinics, surgeries, etc.)?

- Do we judge/grade our degree of errors, ascertain our culpability and seek to prevent recurrence?

- At what time do patients die most: during call duty periods, weekends when all hands may not be on deck?

- Are documentations adequate to capture the last 30 minutes of patients' lives?

- What is the benefit/added value of our continuing education, researches, updates, workshop, conferences and seminars to professional development of medical personnel?

- Has interprofessional wrangling/rivalry not severely compromised patients' care?

- Are there not communication lapses between aggrieved health practitioners?

- Have health workers not abandoned patients' and public interests for research?

- What seeds of professional excellence are systematically sown for the future of the individual professions and corporate practice?

- Do researches really enable evidenced-based medical practice?

- Should there be budgetary modifications to meet present needs and realities?

An autopsy service of acceptable quality should meet the needs of the requesting clinicians, address the problems faced by the health professionals in the management of every case, contribute to the improvement of patient care, answer the questions of relatives of the deceased as best as possible, meet legal requirements as well as ensure the highest standards of practice and safety of the pathologist(36).

Conclusion

Though assessing quality in a multistage exercise like the autopsy may be challenging, a stepwise approach would help in ensuring that quality is maintained in the post-mortem examination. The meticulous attention to details will ensure that this unique clinical care gold standard tool itself indeed remains unassailable and continues to stand out as the veritable assessor that it is meant to be. The autopsy presents the best means of clinicopathologic assessment as it correlates the autopsy findings and clinical diagnoses. Good communication between the pathologists, clinicians, nurses and all health personnel involved in patients' care is advocated on a consistent basis so as to improve care for future patients and for the overall benefit of the healthcare system. Despite the exuberant over-hyping of modern diagnostic techniques and their seeming invincibility claims to detect and diagnose every disease, the autopsy remains the best available forensic tool and its conduct requires the highest possible quality standards.

References

- Croft P, Altman DG, Deeks JJ, Dunn KM, Hay AD, Hemingway H, et al. The science of clinical practice: Disease diagnosis or patient prognosis? Evidence about 'what is likely to happen' should shape clinical practice. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–8.

- EM C. Nurses, Negligence and Malpractice. Am J Nurs. 2003;103(9):54–63.

- Kuijpers CCHJ, Fronczek J, Van De Goot FRW, Niessen HWM, Van Diest PJ, Jiwa M. The value of autopsies in the era of high-tech medicine: Discrepant findings persist. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(6):512–9.

- Tette E, Yawson AE, Tettey Y. Clinical utility and impact of autopsies on clinical practice among doctors in a large teaching hospital in Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):1–7.

- Komolafe AO. The Morphological Basis and Laws of Autopsy Interpretation: Exploring the Relationship between the Basic Medical Sciences, Anatomical Pathology and Clinical Practice. In: Sheriff D.S., editor. Current Trends in Medicine and Medical Research Vol 4. 4th ed. West Bengal: Book Publisher International; 2019. p. 74–9.

- Scordi-Bello IA, Kalb TH, Lento PA. Clinical setting and extent of premortem evaluation do not predict autopsy discrepancy rates. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(9):1225–30.

- Shojania KG; Burton EC; McDonald KM; Goldman L. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289(21):2849–56.

- Komolafe AO, Adefidipe AA, Akinyemi HAM, Ogunrinde O V. Medical Errors Detected at the Autopsy: A Prelude to Avoiding Malpractice Litigations. J Adv Med Med Res. 2018;27(7):1–8.

- Nwafor CC, Nnoli MA CC. Causes and pattern of death in a tertiary hospital in Southeastern Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2014;17(3):102–7.

- Komolafe AO, Adefidipe AA AH. Correlation of antemortem diagnoses and postmortem diagnoses in a preliminary survey - any discrepancies? Niger J Fam Pract. 2018;9(1):105–8.

- Pakis I, Polat O, Yayci N, Karapirli M. Comparison of the Clinical Diagnosis and Subsequent Autopsy Findings in Medical Malpractice. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2010;31(3):218–21.

- Loughrey M, McCluggage W. The declining autopsy rate and clinicians' attitudes. Ulster Med J. 2000;69(2):83–9.

- Daramola AO, Elesha SO, Banjo AAF. Medical audit of maternal deaths in the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(6):285–9.

- Akinwusi PO, Komolafe AO, Olayemi OO, Adeomi AA. Communicable disease-related sudden death in the 21st century in Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist. 2013;6(6):125–32.

- Akinwusi PO, Komolafe AO, Olayemi OO, Adeomi AA. Pattern of sudden death at Ladoke Akintola university of technology teaching hospital, Osogbo, South West Nigeria. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9(1):333–9.

- Davies DJ, Graves DJ, Landgren AJ, Lawrence CH, Lipsett J, MacGregor DP, et al. The decline of the hospital autopsy: A safety and quality issue for healthcare in Australia. Vol. 180, Medical Journal of Australia. 2004. p. 281–5.

- Gorea R. Role of Forensic Nurses in the mortuary and postmortem examination. Int J Ethics, Trauma Vict. 2020;6(01):6–9.

- Maixenchs M, Anselmo R, Sanz A, Castillo P, Macete E, Carrilho C, et al. Healthcare providers' views and perceptions on post-mortem procedures for cause of death determination in Southern Mozambique. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):1–16.

- Bawa-Garba H. EWCA Criminal (2016). 1841.

- Di Nunno N, Patanè FG, Amico F, Asmundo A, Pomara C. The Role of a Good Quality Autopsy in Pediatric Malpractice Claim: A Case Report of an Unexpected Death in an Undiagnosed Thymoma. Front Pediatr. 2020;8(February):4–8.

- Akinwumi Oluwole Komolafe NAT. Autopsy Pathology: General Principles and Interpretation. Niger Clin Rev J. 2008;71(2):31–3.

- Komolafe A.O.; Titiloye N.A. Essentials of Autopsy Pathology. Niger J Fam Pract. 2016;7(1):7–14.

- Adeniran AA, Adegoke OO, Komolafe AO. Cardiac tamponade complicating thoracocentesis: A case for image-guided procedure. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;29.

- Burton JL, Underwood J. Clinical, educational, and epidemiological value of autopsy. Vol. 369, Lancet. Elsevier; 2007. p. 1471–80.

- Goldman L, Sayson R, Robbins S, Cohn LH, Bettmann M, Weisberg M. The Value of the Autopsy in Three Medical Eras. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(17):1000–5.

- Lewis G. Reviewing maternal deaths to make pregnancy safer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(3):447–63.

- De Vlieger GYA, Mahieu EMJL, Meersseman W. Clinical review: What is the role for autopsy in the ICU? Vol. 14, Critical Care. 2010.

- Komolafe A.O.; Titiloye N.A. The role of the pathologist in medical litigations. Niger J Postgrad Med. 2009;2(1):18–25.

- Schröder AS, Wilmes S, Sehner S, Ehrhardt M, Kaduszkiewicz H, Anders S. Post-mortem external examination: competence, education and accuracy of general practitioners in a metropolitan area. Int J Legal Med. 2017;131(6):1701–6.

- Guly HR. Diagnostic errors in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2001;18(4):263–9.

- van den Tweel JG, Wittekind C. The medical autopsy as quality assurance tool in clinical medicine: dreams and realities. Virchows Arch. 2016;468(1):75–81.

- Adeyi OA. Pathology Services in Developing Countries - The West African Experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135(2):183–6.

- Sharma BR, Reader MD. Autopsy Room: A Potential Source of Infection at Work Place in Developing Countries. Am J Infect Dis. 2005;1(1):25–33.

- Croner. Health and Safety at Work. J Clin Pathol. 1998;36:254–60.

- David M. Studdert MMM, Atul A. Gawande TKG, Allen Kachalia CY, and Troyen A. Brennan ALP. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024–33.

- Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, Benson JM, Rosen AB, Schneider E, et al. Views of Practicing Physicians and the Public on Medical Errors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(24):1933–40.